by Jean Daigneau

(Originally appeared in the March, 2023 issue of Children’s Book Insider, the Children’s Writing Monthly)

Many of us grew up with fairy tales, either written or oral. For younger writers, fractured fairy tales might be more familiar. Fractured fairy tales are written as a parody of the original story or a tongue-in-cheek version. Often they are told from a different point of view and presented with a humorous twist, such as Jon Scieszka’s picture book, The True Story of the Three Little Pigs.

Long before written fairy tales, folktales were recited and often reenacted to teach lessons, make sense of nature, and explain the unknown. In the earliest communities, these stories were shared by elders or storytellers—called griots in West African culture. The oldest evidence of storytelling dates back about 44,000 years to an Indonesian cave painting, depicting human hunters with animal features—“therianthropes”—which have appeared in numerous myths across many cultures. Let’s learn more.

A Long and Well-Traveled History

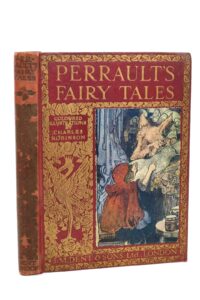

Fairy tales and folktales, passed down for thousands of years, changed and evolved with each retelling. French folklorist Charles Perrault is credited with creating the first written fairy  tales in his 1697 book, Mother Goose. His stories, including Little Red Riding Hood and The Sleeping Beauty, were adapted and published from somewhat forgotten folktales. Of course, the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, among others, wrote, published, and memorialized many stories known today. But, details often changed with subsequent versions throughout time and place—a kind of evolutionary global game of telephone.

tales in his 1697 book, Mother Goose. His stories, including Little Red Riding Hood and The Sleeping Beauty, were adapted and published from somewhat forgotten folktales. Of course, the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, among others, wrote, published, and memorialized many stories known today. But, details often changed with subsequent versions throughout time and place—a kind of evolutionary global game of telephone.

Research indicates between 800 and 900 versions of Cinderella in existence. Think about the cultural differences between a Guatemalan tribal elder enacting that story and a spice trader sharing a version in China. Early tales often included dark and violent details. They had sinister plots, graphic violence, and sometimes dismal endings. An early version of Hansel and Gretel had the children sent by their parents into the woods to starve. In one Swiss version, Snow White is accused of sleeping with the dwarves. Not necessarily acceptable for young readers today.

The folktales Perrault and others borrowed from often were intended to teach lessons and highlight cultural values. They usually showed characters making life-changing decisions, with the intent of showing how “good” decisions led to meaningful and fulfilling lives, while “poor” decisions resulted in serious consequences. Historically, villages or tribal people depended on cooperation among members for the entire community’s survival. Poor decision-making could result in serious issues for everyone. The lessons about good decision-making, handed down from family members, storytellers, and community elders, were crucial, even as they evolved with changing times.

Writing the Modern Tale

Today’s fairy tales share some elements of earlier versions. In both cases, the main character and the action have to be believable. The original version of Beauty and the Beast, written in 1740 by a French author and actually based on a true story, might not have survived if early readers were unable to buy into the believability of a so-called “beast” covered in hair, who could find love with a beautiful woman. As with any story, readers must be vested in their main character’s situation to work.

In contrast to early versions, however, today’s main characters and actions are often complex and convoluted; early characters were more one-dimensional. Settings from stories long-ago might simply reference a castle or the dark woods, while today’s settings can play an integral role. But almost always, the focus was and is usually on ordinary people having extraordinary adventures. And most stories are rarely told without a villain who attempts to thwart the protagonist at every turn.

Keep in mind, if you’re considering this genre, that while some of today’s books have a moral, they can also entertain for entertainment’s sake. In fact, picture book author and folklorist Eric A. Kimmel says, “That’s the problem with so many children’s books today…. The moral comes at you with the subtlety of a freight train.” No reader wants that, unless they’re reading Aesop’s Fables.

When drawing on old tales, middle-grade novelist Shakirah Bourne believes, “You have more flexibility to adapt the mythology to whatever makes sense for the story. Just as others have done, you can put your own spin on the characteristics of the folk characters and adapt them to make them more relatable and relevant to kids today.” For instance, fairy tales today might feature strong but flawed, independent females or transgender characters. And since original folk and fairy tales are not copyrighted, you can borrow as much or as little from them as needed. Your version might include a plot twist, a new villain, or a contemporary setting.

Additionally, today’s fairy tales don’t always end happily ever after. Especially for middle-grade and young adult readers, plots can be dark and dangerous, as long as they have all the elements of a good story.

Folktales in a Changing World

Kimmel has written over 150 books for kids and received numerous awards. He loved stories told by his grandmother “in three different languages: Yiddish, Ukrainian, and Polish.” Kimmel notes that he’d “do chores and she’d tell stories,” and when he pointed out a different version of a familiar story, she simply said, “That’s how I told it then. This is how I’m telling it now.” The evolving story in the flesh.

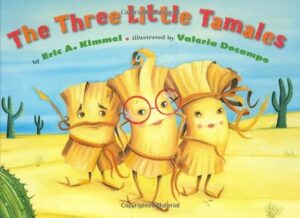

Kimmel’s books, which span many cultures, lean toward classic retellings that may change the setting or characters but retain key plot elements of the original. For example, his The Three Little Tamales is a Southwestern version of The Three Little Pigs, and his highly acclaimed stories about Anansi the Trickster infuse tales originating in West Africa and Caribbean culture with slapstick humor and mischief.

Little Tamales is a Southwestern version of The Three Little Pigs, and his highly acclaimed stories about Anansi the Trickster infuse tales originating in West Africa and Caribbean culture with slapstick humor and mischief.

But he also acknowledges that today, “Enormous changes have taken place in children’s publishing.” He noted, “The story picture book—an illustrated book for older readers—is just about extinct. Graphic novels have taken their place.” While he continues to publish with small Jewish presses, he says this about publishing folktales today, “I’ve found within the last ten years that there’s just no market for folktales. Or at least not the ones I write.” In other words, the wave of highly-illustrated traditional folk and fairy tale retellings that spanned from the mid-1980s to about 2010 (fueled by the talents of authors and illustrators like Fred Marcellino, James Marshall, Jerry Pinkney, Paul O. Zelinsky, Janet Stevens, Ed Young, and Eric A. Kimmel) have evolved into something else.

A New Take on an Old Tale

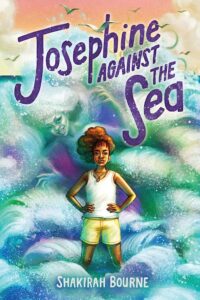

For today’s readers, authors are often reinventing fairy and folktales to inspire new stories, without being too tied to the originals’ details. Bourne, author of Josephine Against the Sea and  Nightmare Island, weaves elements of Caribbean mythology through modern middle-grade plots.

Nightmare Island, weaves elements of Caribbean mythology through modern middle-grade plots.

Bourne draws on her Caribbean nationality and its history of storytelling. “My ideas come from everywhere: observing society and the people around me, reading books and researching history, or scrolling through social media.”

Besides her own culture, she says, “I also examine issues that kids typically deal with—for example, peer pressure, anxiety, self-acceptance—and try to make sure my characters have to deal with these challenges as well.” Those issues reflect the world of tweenand teen readers across the globe. Of her own books, she notes, “I also wanted the stories to be fun; I had read more than enough books in school that only focused on trauma.”

But Bourne also advises that “sometimes, a mythological character isn’t a ‘myth’ to everyone, especially when it is based on the history of a group of people and represents their religious beliefs. It is important to be respectful to the character in how you portray them in the story so as to not offend an entire community, especially if you are not a member of said community.”

Fairy or Fractured, But Not Broken

Fractured fairy tales (those parodies of the original story) are another way to explore new approaches that still work. Fractured fairy tales DO retain enough details of the original for readers to recognize which story is being skewered, but also exaggerate or twist the elements so the plot goes in an unexpected direction. Here are things to consider when conjuring up a fractured or modern tale: What misunderstood protagonist or secondary character can you draw on for your story? What culture can you research or adapt from your own ancestry for the setting? What plot twists can push a conventional tale in a new direction? Or what spin can you put on a classic ending to mix things up and delight your readers? Humor—puns, exaggerated situations, silly jokes, sarcastic narrators—is key to making fractured tales work.

Whatever approach you take, don’t become complacent because you’re relying on long-told fairy tales, family stories, or cultural tales. Bourne says, “After scouring the internet, which often repeats the same information, the best way to do research is by talking to elders and asking the community about tales they heard growing up.” While we all might not have access to village elders, Bourne found that “a few myths are well-documented since they are based on supposed true events in history. For one book, I spent weeks exploring our National Archives, reading ledgers, journals, and old newspapers to get firsthand testimonies. I even went as far as looking at wills for persons involved in the supernatural event.”

Finding Your Happily Ever After

Reimagined versions of fairy and folktales can still work today. As Kimmel advises, “Rule #1: There are no rules. Rule #2: When in doubt, remember the first rule.” Recapture the fun of the recently celebrated National Fairy Tale Day, February 26th, by stretching your creativity and rethinking your favorite childhood tale. You might just discover a villain who wants to set the story straight.

✏ Word Counts & Age Groups for Every Kidlit Category

✏ FAQs, Glossaries and Reading Lists

✏ Category-specific Tips, from Picture Books Through Young Adult Novels

✏ 5 Easy Ways to Improve Your Manuscript

✏ Writing For Magazines …and more!

This is a gift from the editors of Children’s Book Insider, and there’s no cost or obligation of any kind.

We will never spam you or share your personal information with anyone. Promise!