Many authors, whether they’re published or not, would be thrilled to find out their latest manuscript is headed for a contract. If the publishing house is interested in a two- or three-book series, the joy increases exponentially. While a book “series” is not a genre, I’m going to exercise poetic license and call the focus of this month’s column fiction, with a slant toward series. Who doesn’t want to know more about a contract that might include a duo- or multibook deal, right?

The Chicken or the Egg?

When authors talk about writing a series, the question that invariably comes to mind is: “Did you start out writing a series or did you pitch as a standalone?” First, we need to establish there are actually two definitions to series writing.

One type of series, such as Sage Underwood’s Jinx series, continues one storyline over several books. While each book can stand alone and has its own story arc, the main story thread is not resolved until the end of the last book, however many books that takes. New characters may be introduced, but the action (mostly) resolves around the main character and the journey she embarks on. Along with that is a series arc, which is just what it implies. Another arc that spans the entire series.

The other kind of series–which is most often seen with chapter books or early middle grade novels– involves the same character, but may involve a reoccurring setting, a cast of supporting characters, or what could be called the same “reality.” On the flip side, the location where the action occurs may change or new characters might be introduced. But there is a common element that connects these stories, centered around the main character. Series that fall into this category, such as Tricia Springstubb’s Cody series, involve different conflicts in each book that are resolved in that one book.

You Have to Stand on Your Own Two Feet

Stephanie Greene has written four series, including Owen Foote and Princess Posey. For her, the success of the first book of each series is what led to her editor recognizing the series potential. While Greene initially had ideas for other books involving her characters, she says, “I know well how annoying it is for editors to be told in query letters that this fantastic! (unknown author’s) book is only the first of 10!” Greene believes the editor should determine that unless, she says, “you’re a well-known author.”

Interestingly, both Underwood and Springstubb took a different approach. For Springstubb, her agent told her a standalone doesn’t work well for early middle grade novels; because the books are so short, it’s too easy for a standalone to get overlooked. Instead, the agent pitched a two-book series that turned into four. Underwood queried her Jinx project to agents as a “standalone with series potential,” but once she got an agent, the agent opted to pitch it as series from the start.

Love It or Leave It

It can be tempting to think that writing a series is as easy as putting a good character into a few new situations and the result will be books that readers will return to again and again. Greene says, that generally speaking, that’s true, “assuming the character is terrific and the new situations are, too, of course. Oh, and that the writing’s good and the dialogue is believable, and the suspense is riveting or the humor hilarious.”

In reality, the challenges to writing a series may surprise you. Because you’re going to be spending a lot of time with your protagonist, you need to love him. Additionally, your character must show growth in every story, another challenge. But in a series for younger readers, with characters like Cody and Princess Posey, you actually could disappoint your readers if your character changes too much. So, the challenge is to keep things fresh without losing sight of the character your fans fell in love with in the first place.

Another caveat authors need to avoid is to keep from getting bored…themselves! Springstubb says for her, it’s not an issue, because she follows her characters over time and is always discovering new things about them. But, “if a writer is bored or on automatic pilot, readers will feel the same way.” The last thing you want to do is write a knock-out first book and then slack off with subsequent books. That’s one of the quickest ways to lose readers.

Underwood has a technique she uses that has worked well through her three-book series. To keep her readers engaged, she says, “I try to keep them laughing….In general, don’t spend more than two sentences on description and try not to let a character speak more than one and a half sentences at a time.”

Continuity is Key

One issue with writing a series is losing track of what might seem like minor details. While it’s easy for an author to forget a personality quirk or even a physical trait from book one to book three, your readers aren’t going to forget. They’ll catch contradictions every time and you wouldn’t be the first author to be called out on it.

Underwood avoids falling into this trap by using “lots of post-it notes.” With index cards, she makes columns down a wall, using different colored ink for each primary character. For her, it’s a way to “follow his or her development and, at a glance, cross-reference it to what was going on with the other characters in the story.”

Then, too, a character that has never been able to shape shift should not suddenly acquire that skill in the final book, simply because it’s needed to make a scene or conflict work. One way to work around this is to plant seeds early so that something that happens later in a series is plausible and logical. At all costs, these kinds of elements must be believable, whenever they appear.

Unlike a series with characters like Cody and Posey who don’t age much, a character in a series that spans several books often does age. Your reader will buy into an aging character, but his transformation, and physical growth, must work within the story world you’ve created for him.

Things Worth Considering

Something to consider when writing a series is that as time passes, things change. The reality of a five or seven-book series being published is relatively unheard of today. What only a few years ago was common for fantasy–trilogies–now more often than not has changed to duologies. Not that the market can’t swing the other way again, but don’t lose out on a book deal because you’re married to the idea of writing a series.

One thing that Underwood learned in the course of her series is that while a first book can garner awards, subsequent books in the series are often overlooked. She found that “it’s not at all unusual for series books to receive no industry review at all, after the first book.”

Regarding series writing, Springstubb’s best advice is to “create a character you deeply love” because “if you’re lucky, you’ll be spending a lot of time with her!” As with any book, Greene says, “Concentrate on writing a single book that’s so good, your editor will ask for more.”

For further reading:

The Young Elites series (Marie Lu)

Lucy’s Lab series (Michelle Houts)

Five Kingdoms series (Brandon Mull)

Children of Exile series (Margaret Peterson Haddix)

The Trials of Apollo series (Rick Riordan)

The Brotherband Chronicles series (John Flanagan)

Dog Man series (Dav Pilkey)

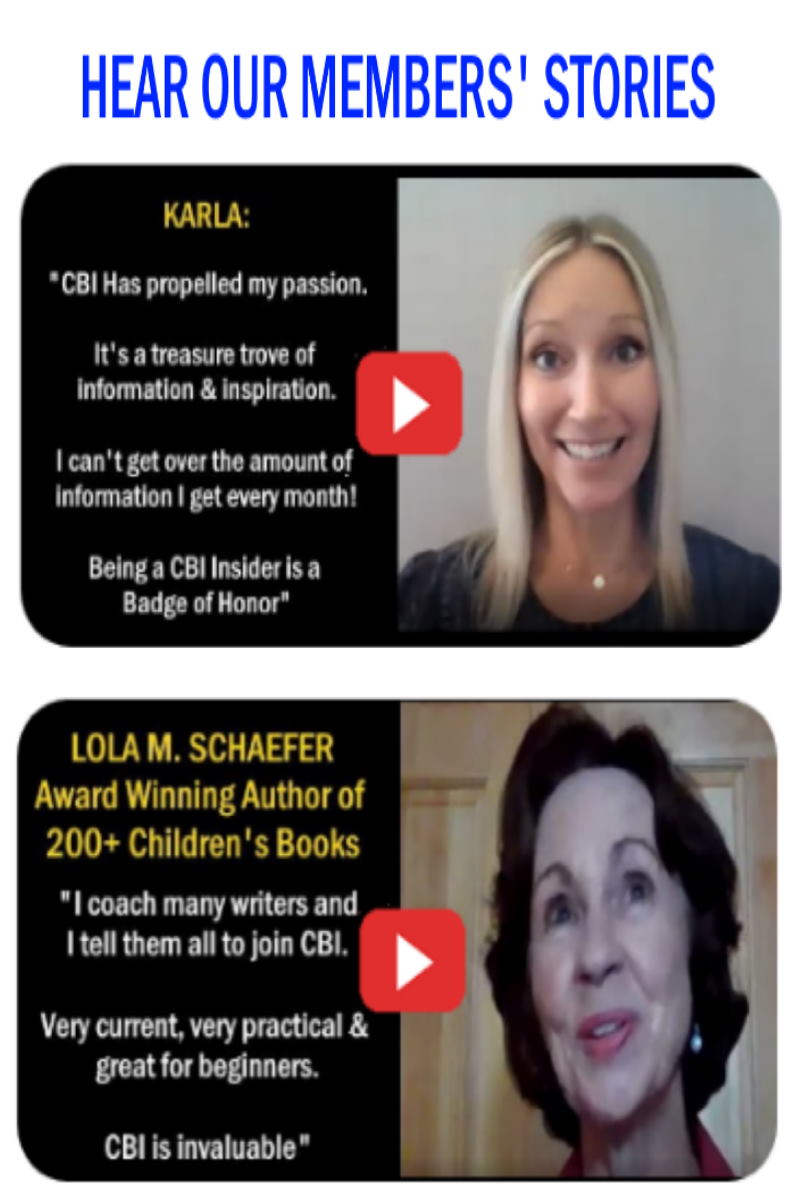

Reprinted from Children’s Book Insider, the Children’s Writing Monthly

✏ Word Counts & Age Groups for Every Kidlit Category

✏ FAQs, Glossaries and Reading Lists

✏ Category-specific Tips, from Picture Books Through Young Adult Novels

✏ 5 Easy Ways to Improve Your Manuscript

✏ Writing For Magazines …and more!

This is a gift from the editors of Children’s Book Insider, and there’s no cost or obligation of any kind.

We will never spam you or share your personal information with anyone. Promise!

Writing a fiction series for children’s books sounds exciting and challenging! From what I’ve studied, there are so many dimensions you need in order to make this successful, and I look forward to exploring this area more. Thanks for sharing this article, Jean!